Integrating genomics into the U.S. Endangered Species Act

|

As part of my David H. Smith Conservation Research Fellowship, I helped develop guidelines and analytical tools that allow for more effective integration of genomic data into U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) decision-making. Working in close collaboration with colleagues from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and National Marine Fisheries Service, this research took advantage of the novel insights available from genomic data, while addressing the challenges and uncertainties they pose for existing frameworks for conserving biodiversity under the ESA.

We have (so far) published a review of evolutionary potential and extinction risk, a book chapter reviewing the role of genomics in the past, present, and future of ESA decision-making, as well as a simulation study evaluating the impact of evolutionary potential in response to climate change for the southwestern willow flycatcher. This research follows up on our publication on adaptive potential and the ESA. |

Landscape and conservation genomics of imperiled frogs

|

My first postdoctoral research position, based in Chris Funk's lab at Colorado State University, had two parts: investigating the evolutionary ecology and genomic basis of thermal tolerance in tailed frogs (genus Ascaphus); and conservation and landscape genomics of the Great Basin Distinct Population Segment of the Columbia spotted frog (Rana luteiventris).

The Ascaphus project is an ongoing, collaborative effort to uncover spatial patterns of vulnerability using an integrative framework that links environmental heterogeneity to genetic and phenotypic variation in resilience traits. Working across multiple data sets, including high resolution spatial and temporal stream temperature data, physiological, and genomic data, we are forecasting population-level resilience and vulnerability to climate change using individual-based landscape genomic simulations. I also used genomic methods to better delineate conservation units within the Great Basin Distinct Population Segment of the Columbia spotted frog. In this project, we used genomic, spatial, and environmental data to better understand population connectivity, genetic diversity, and local adaptation, with the goal of identifying conservation and management units within Nevada. This project included collaborators from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Geological Survey, Nevada Department of Wildlife, and Nevada Natural Heritage Program. |

Adaptive capacity of terrestrial salamanders in the face of climate change

|

Faced with climate change, organisms must adapt in place or move—or they go extinct. Relative to dispersal, adaptation in response to environmental change remains poorly understood. Fortunately the recent development of molecular techniques for detecting local adaptation in wild populations has made it easier to evaluate this response. These tools offer important benefits for conservation practice in a dynamic world, since conserving adaptive capacity and evolutionary potential can improve the capacity for species to persist under the synergistic effects of climate change and habitat fragmentation.

I investigated the interaction of local adaptation and gene flow in two species of terrestrial salamanders (which lack lungs and breathe through their skin): Plethodon cinereus (the red-backed salamander) and Plethodon welleri (Weller's salamander, a species of conservation concern). Plethodontid salamanders have limited dispersal capabilities, narrow physiological tolerances, and are highly sensitive to changes in climate. In eastern North American forests, they are the dominant and most abundant vertebrate predators, where they play a fundamental role in ecosystem structure, function, and stability. These characteristics—environmental sensitivity and ecological importance—make them an excellent indicator taxon for climate change research. My research quantified how local adaptation and gene flow interact to affect the evolutionary potential of these species in fragmented and warming habitats. This work helps us better understand the capacity of species to adapt to climate change, and what actions will be most effective to conserve biodiversity under global change. |

Genotype-environment associations: detecting the genomic basis of local adaptation

|

I am working with a group of colleagues to test the increasing number of statistical methods for detecting markers under selection. Our focus is on their effectiveness in non-model species in a landscape genomic context.

Our most recent article tests multivariate and machine learning GEA methods. Some of these are more effective at detecting important adaptive processes, such as selection on standing genetic variation, that result in weak, multilocus signatures. We have an earlier publication that investigates the role of landscape heterogeneity in generating patterns of local adaptation, and tests a suite of multivariate GEAs. Our first paper combined spatial analyses with GEA, providing a powerful approach for identifying candidate loci and explaining spatially complex interactions between species and their environment. |

Projecting climate change impacts using ensemble species distribution models and statistical phylogeography

|

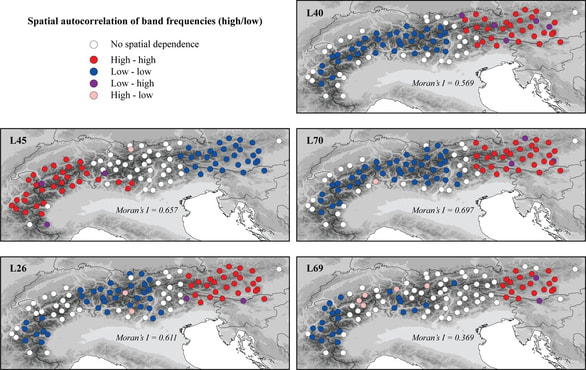

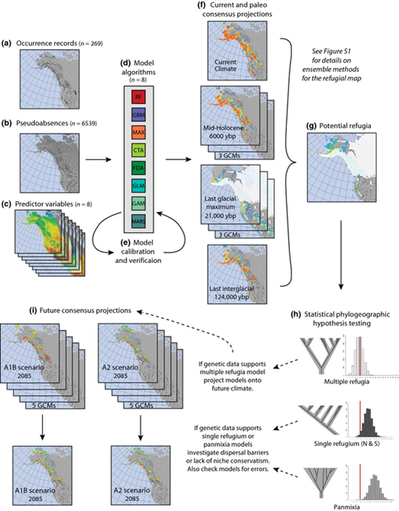

Species distribution models (SDMs) are commonly used to forecast climate change impacts. These models, however, are subject to important assumptions and limitations. By integrating two independent but complementary methods, ensemble SDMs and statistical phylogeography, we addressed key assumptions and created robust assessments of climate change impacts on the arctic-alpine plant Rhodiola integrifolia, while improving the conservation value of these projections. Integrating molecular approaches with spatial analyses has great potential to improve conservation decision-making. Molecular tools can support and improve current methods for understanding the vulnerability of species to climate change and provide additional data upon which to base conservation decisions, such as prioritizing the conservation of areas of high genetic diversity to build evolutionary resiliency within populations. This research was part of my Master's degree thesis at the College of the Environment at Western Washington University. |

Restoration ecology of an urban stream corridor in response to a catastrophic burn event

|

On June 10, 1999 an underground pipeline ruptured in Bellingham, Washington, releasing approximately 237,000 gallons of unleaded gasoline into Hannah and Whatcom Creeks. The gasoline was subsequently ignited, resulting in an explosion. The incident killed three people, and burned 26 acres of riparian zone. All aquatic life in three miles of Whatcom Creek was killed through direct contact with the fuel or fumes, or when the fuel ignited.

A Long-term Restoration Plan was established to determine the impacts of the spill on natural resources and identify measures that would be implemented to restore those injured resources. The goals for rehabilitation and enhancement centered on mitigating damages by creating and improving salmonid habitat associated with Whatcom Creek. I conducted monitoring work on restoration sites associated with the pipeline explosion. This diverse research included biotic surveys (vegetation, spawning adult salmon, juvenile salmon (smolt trapping), aquatic macroinvertebrates, amphibians, birds, and mammals) and physical surveys (pond bathymetry, channel morphology, in-stream salmonid habitat conditions, and water quality). Reports covering the first three years of monitoring work are linked below: Forester BR (2009) Whatcom Creek Restoration Project Report: 2009. Technical Report. City of Bellingham, Washington. 110 pp. PDF. Forester BR (2008) Whatcom Creek Restoration Project Report: 2007-2008. Technical Report. City of Bellingham, Washington. 133 pp. PDF. |